Return to 1258 Part One

Simon de Montfort as a Revolutionary ?

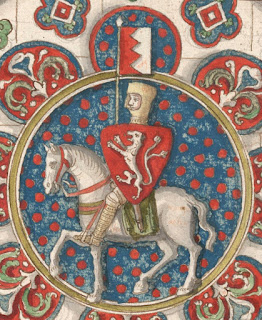

Drawing of a stained glass window of Chartres Cathedral, depicting Simon de Montfort, courtesy Wikipedia

This is a first of a serious of posts about 1258, and how this year radically changed the way England was governed. Amongst the reforms achieved were that a Council of fifteen was to be elected who would have the right to choose who the King appointed as ministers and could regulate the use of the King's seal. It's hard to find evidence of such an arrangement in other European countries. Parliament was to meet three times a year on fixed dates.

The harsh weather conditions as from 1257 and the ghastly famine of the time has been already covered in this blog. The barons challenge to the kingship of Henry III in 1258 did not lead to civil war- in fact the related conflict usually known as the Second Barons War- did not break out until 1264. Yet 1258, saw the crucial reforms that led to the strengthening of parliament and measures to ensure that the Crown was far more accountable. And initially Henry III was prepared to compromise. Yet when war came, it brought two major pitch battles : On 14th May 1264 the royalist army was defeated by a rebel alliance led by Simon de Montfort. Henry III, his brother Richard Duke of Cornwall, and the heir to the throne Lord Edward ( future King Edward I) were taken prisoner.

For nearly 15 months, Simon de Montfort was the most powerful figure in the country, but effectively ruled in the king's name , and further reforms were implemented. However disagreements broke out amongst the rebels and de Montfort's power basis was reducing. The threat of a foreign invasion was prevalent, though arguably gained more popular support for the new regime. Lord Edward escaped from captivity on 28th May 1265. On 4th August 1265, Simon de Montfort 's army was defeated at the Battle of Evesham by Edward's forces. De Montfort was killed in battle, along with one of his sons, and at least thirty other members of the nobility. Yet the conflict would not be fully brought to a close until 1267.

Recent historians have highlighted the significance of 1258:

J.RMaddicott stated in his excellent biography on de Montfort :

" The reform movement of 1258 was the most radical assault yet made on the perogatives of the Crown, and one which brought England nearer to a republican constitution than at any time before 1649. The is not a development which had at the outset been either intended or foreseen."

Darren Baker, in 'With All For All-The Life of Simon de Montfort' (2015), referred to 1258 as

"the beginning of a political revolution that put power and privilege, long engrained in the social fabric, through the grinder of widespread dissatisfaction."

The latest de Montfort biography is Sophie Therese Ambler's 'The Song of Simon de Montfort, England's First Revolutionary and the Death of Chivalry' (2019) : A vital first step in looking at 1258 onward is to look at what terms such as 'revolutionary' and 'radical' mean when tackling dramatic events in the 13th century. What associations are made to readers from the 21st century when using these descriptors ? Would Simon de Montfort himself , the barons who backed him, those who served in armies he commanded at ,his supported within the Church, ever regard themselves as fighting for a different social, economic order? If so, what alternative model of society did they have in mind? And there is little evidence to suggest that future English radicals ever viewed themselves as the heirs to Simon de Montfort.

Another interpretation is that radical change happened to the form of English government by default -ones that were not originally "intended or foreseen" to use J.R.Maddicott's words. So de Montfort and his associates become radicals or revolutionaries by default, without a clear ideology? Certainly de Montfort -who was of course brother in law to Henry III and Earl of Leicester-has been dismissed as being a discontented magnate obsessed by his own self advancement, rather than advocating any serious reforms. And just about all English radical movements from the uprising of 1381 ( the 'Peasants Revolt') involve mass participation of the Common people , not just a faction of disgruntled nobility and whoever they could cajole or persuade to fight for them.

A major consideration is that in looking at the 13th century, it is harder to determine human motives because we have little evidence where people have written about themselves . We are very unlikely to find a stash of letters, written diaries, a bundle of political tracts, where the de Montfort family and supporters have expressed their own thoughts, as if we were studying the Levellers or Diggers of the 17th century or modern day revolutionaries. Yet there is source material out there; charters, Court rolls, chronicles written by clerics, the odd poem or song lyric that has survived. Somehow the whole right of the Crown to govern was being curbed, and conditions imposed upon the King.

The purpose of this series of posts is to advance the case that Simon de Montfort was a revolutionary for his time and that the reforms of 1258 represented a clear break from the past and the role of the Crown. The written proclamations of the year , most notably the Oxford Provisions that were written in French, Latin and Middle English, demonstrate an intention to create a different political order which encouraged great participation amongst people who were not already born into nobility.

Furthermore, we don't know why there was a significant contingent of Londoners fighting against King Henry III at the Battle Of Lewis or much about them. We don't know their names, or what they thought about the conflict. Usually assumed to be apprentices, and badly armed. But their presence suggests that these were not merely barons and their retainers taking up arms against the Crown. Once de Montfort was killed at Evesham, a miracle cult arose which again leads to the conclusion that there was a some popular support for him and the cause of reform generally.

Just one aside. Though historians including J.R.Medicott and Sophie Therese Ambler have maintained that it would take until the 1640's to see such a challenge to the power of the Crown, I personally would suggest that the Ordinance of 1311, imposed on Edward II by rebel barons, should not be neglected.

To be continued.

The views ( and any mistakes) expressed are mine alone. The writers of works I have cited may well have different opinions to mine .

Michael Bully , Brighton 12th March 2020

Main works consulted

Sophie Therese Ambler ' The Song of Simon de Montfort -England's First Revolutionary and the Death of Chivalry' Picador 2019

Darren Baker 'With All For All-The Life of Simon de Montfort ' Amberley 2015

J.R. Maddicott 'Simon de Montfort ' Cambridge University Press 2015

Sir Maurice Powicke 'The Thirteenth Century 1216-1307' Clarendon Press 1953

Simon de Montfort Society Website

The Simon de Montfort Society

Other blogs run by Michael Bully

A Burnt Ship 17th century war & literature

Bleak Chesney Wold Charles Dickens/ 'dark' 19th century history

Drawing of a stained glass window of Chartres Cathedral, depicting Simon de Montfort, courtesy Wikipedia

This is a first of a serious of posts about 1258, and how this year radically changed the way England was governed. Amongst the reforms achieved were that a Council of fifteen was to be elected who would have the right to choose who the King appointed as ministers and could regulate the use of the King's seal. It's hard to find evidence of such an arrangement in other European countries. Parliament was to meet three times a year on fixed dates.

The harsh weather conditions as from 1257 and the ghastly famine of the time has been already covered in this blog. The barons challenge to the kingship of Henry III in 1258 did not lead to civil war- in fact the related conflict usually known as the Second Barons War- did not break out until 1264. Yet 1258, saw the crucial reforms that led to the strengthening of parliament and measures to ensure that the Crown was far more accountable. And initially Henry III was prepared to compromise. Yet when war came, it brought two major pitch battles : On 14th May 1264 the royalist army was defeated by a rebel alliance led by Simon de Montfort. Henry III, his brother Richard Duke of Cornwall, and the heir to the throne Lord Edward ( future King Edward I) were taken prisoner.

For nearly 15 months, Simon de Montfort was the most powerful figure in the country, but effectively ruled in the king's name , and further reforms were implemented. However disagreements broke out amongst the rebels and de Montfort's power basis was reducing. The threat of a foreign invasion was prevalent, though arguably gained more popular support for the new regime. Lord Edward escaped from captivity on 28th May 1265. On 4th August 1265, Simon de Montfort 's army was defeated at the Battle of Evesham by Edward's forces. De Montfort was killed in battle, along with one of his sons, and at least thirty other members of the nobility. Yet the conflict would not be fully brought to a close until 1267.

Recent historians have highlighted the significance of 1258:

J.RMaddicott stated in his excellent biography on de Montfort :

" The reform movement of 1258 was the most radical assault yet made on the perogatives of the Crown, and one which brought England nearer to a republican constitution than at any time before 1649. The is not a development which had at the outset been either intended or foreseen."

Darren Baker, in 'With All For All-The Life of Simon de Montfort' (2015), referred to 1258 as

"the beginning of a political revolution that put power and privilege, long engrained in the social fabric, through the grinder of widespread dissatisfaction."

The latest de Montfort biography is Sophie Therese Ambler's 'The Song of Simon de Montfort, England's First Revolutionary and the Death of Chivalry' (2019) : A vital first step in looking at 1258 onward is to look at what terms such as 'revolutionary' and 'radical' mean when tackling dramatic events in the 13th century. What associations are made to readers from the 21st century when using these descriptors ? Would Simon de Montfort himself , the barons who backed him, those who served in armies he commanded at ,his supported within the Church, ever regard themselves as fighting for a different social, economic order? If so, what alternative model of society did they have in mind? And there is little evidence to suggest that future English radicals ever viewed themselves as the heirs to Simon de Montfort.

Another interpretation is that radical change happened to the form of English government by default -ones that were not originally "intended or foreseen" to use J.R.Maddicott's words. So de Montfort and his associates become radicals or revolutionaries by default, without a clear ideology? Certainly de Montfort -who was of course brother in law to Henry III and Earl of Leicester-has been dismissed as being a discontented magnate obsessed by his own self advancement, rather than advocating any serious reforms. And just about all English radical movements from the uprising of 1381 ( the 'Peasants Revolt') involve mass participation of the Common people , not just a faction of disgruntled nobility and whoever they could cajole or persuade to fight for them.

A major consideration is that in looking at the 13th century, it is harder to determine human motives because we have little evidence where people have written about themselves . We are very unlikely to find a stash of letters, written diaries, a bundle of political tracts, where the de Montfort family and supporters have expressed their own thoughts, as if we were studying the Levellers or Diggers of the 17th century or modern day revolutionaries. Yet there is source material out there; charters, Court rolls, chronicles written by clerics, the odd poem or song lyric that has survived. Somehow the whole right of the Crown to govern was being curbed, and conditions imposed upon the King.

The purpose of this series of posts is to advance the case that Simon de Montfort was a revolutionary for his time and that the reforms of 1258 represented a clear break from the past and the role of the Crown. The written proclamations of the year , most notably the Oxford Provisions that were written in French, Latin and Middle English, demonstrate an intention to create a different political order which encouraged great participation amongst people who were not already born into nobility.

Furthermore, we don't know why there was a significant contingent of Londoners fighting against King Henry III at the Battle Of Lewis or much about them. We don't know their names, or what they thought about the conflict. Usually assumed to be apprentices, and badly armed. But their presence suggests that these were not merely barons and their retainers taking up arms against the Crown. Once de Montfort was killed at Evesham, a miracle cult arose which again leads to the conclusion that there was a some popular support for him and the cause of reform generally.

Just one aside. Though historians including J.R.Medicott and Sophie Therese Ambler have maintained that it would take until the 1640's to see such a challenge to the power of the Crown, I personally would suggest that the Ordinance of 1311, imposed on Edward II by rebel barons, should not be neglected.

To be continued.

The views ( and any mistakes) expressed are mine alone. The writers of works I have cited may well have different opinions to mine .

Michael Bully , Brighton 12th March 2020

Main works consulted

Sophie Therese Ambler ' The Song of Simon de Montfort -England's First Revolutionary and the Death of Chivalry' Picador 2019

Darren Baker 'With All For All-The Life of Simon de Montfort ' Amberley 2015

J.R. Maddicott 'Simon de Montfort ' Cambridge University Press 2015

Sir Maurice Powicke 'The Thirteenth Century 1216-1307' Clarendon Press 1953

Simon de Montfort Society Website

The Simon de Montfort Society

Other blogs run by Michael Bully

A Burnt Ship 17th century war & literature

Bleak Chesney Wold Charles Dickens/ 'dark' 19th century history

This looks to be an intriguing blog. I have long been intrigued by how Simon changed the ideas of governance - of constraints on power. Apart from the Magna Carta initiatives (soon watered down) there was little in England to predict this, or in Simon's native France. Indeed it is measure of how radical the change was (in my opinion) that Simon lost the backing of the other barons when they realised that the constraints were meant to apply to themselves as well as to the king. (As well as his fondness for money, of course)

ReplyDelete